Another monochrome aerial view from 1968, Clouds, provides glimpses of an abtsracted version of the German countryside - imagery that Godfrey compares to the opening sequence (above) of Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will (1935). Two years later Richter began a very different series of cloud paintings, this time treating them as isolated objects, white against featureless blue-green skies. They resemble Alfred Stieglitz's famous cloud photographs, Equivalents (1927), which in turn (as Rosalind Krauss points out in that weighty tome Art Since 1900) could be viewed as Duchampian readymades - uncomposed and detached from their environment. Alps II (1968) might be a close-up of a storm cloud and is barely recognisable as a landscape painting, certainly a long way from the heroic image of German mountains celebrated in those early Reifenstahl films.

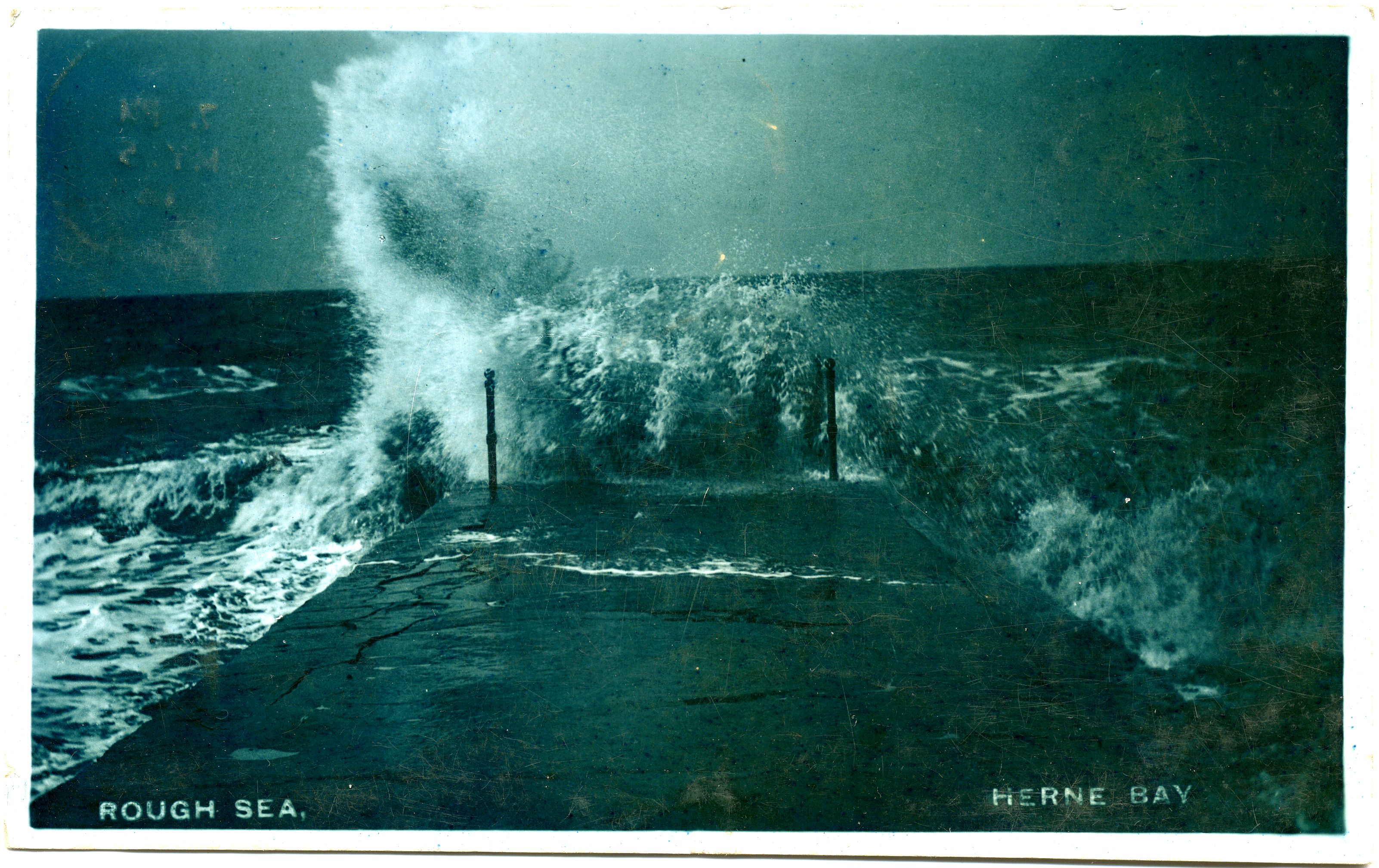

Seascape (Sea-Sea) (1970) is described in the exhibition as a 'collage of two photographs of the sea, one inverted to appear as the sky. The painting creates a momentary illusion of a coherent seascape, until it becomes clear that the ‘clouds’ in the upper half of the painting are waves. It creates a sense of discontinuity and suggests Richter’s acknowledgement of the gulf separating him from the moment of Romanticism.' It made me think of Rothko's grey paintings, with the patterns of waves replacing Rothko's brushtrokes. Mark Godfrey views them as a cross between Capar David Friedrich and Blinky Palermo: an attempt at the kind of radical abstract statement Palermo was making in his Cloth Paintings using the traditional medium of a seascape. Another point of comparison is Vija Celmins and, like her, Richter also produced images of black and white fields of stars.

In 1971 an exhibition of Richter's recent work, painted in flat colour rather than black and white, prompted various critics to compare him with Friedrich. Landscape near Hubbelrath (1969), for example, shows an empty view with a road sign where we expect to see, in Friedrich, a church spire. Richter said that his art lacked the spiritual underpinnings of Romanticism: 'for us, everything is empty'. However, Mark Godfrey argues that Richter and Friedrich both aimed to create a sense of unfulfilled desire (readers of this blog may recall an earlier post on the way Friedrich composed 'obstructed views'). This approach may have seemed particularly appropriate to a post-war German artist working at a time when the purpose of painting itself was being called into question.

There is one more interesting example of Richter's engagement with Friedrich later in the exhibition, a painting called Iceberg in Mist (1982). I have mentioned various artists here before who went north to paint the Arctic seas - Peder Balke, Lawren Harris, Per Kirkeby - and Richter made his own trip in 1972, looking for a motif as powerful as Friedrich's The Sea of Ice. Mark Godfrey mentions that on his return Richter made 'an extraordinary and little-known book of black and white photographs of icebergs', printed, like the two halves of Seascape (Sea-Sea), both upside down and right side up. In this way Richter rejected the single sublime image and arranged the photographs in such a way that 'their overt subject became more or less irrelevant.' Richter's urge to thwart our desire for spectacular landscapes is also evident in the later painting, where we cannot even glimpse the tip of the iceberg as the whole view is shrouded in mist.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice, 1823-4