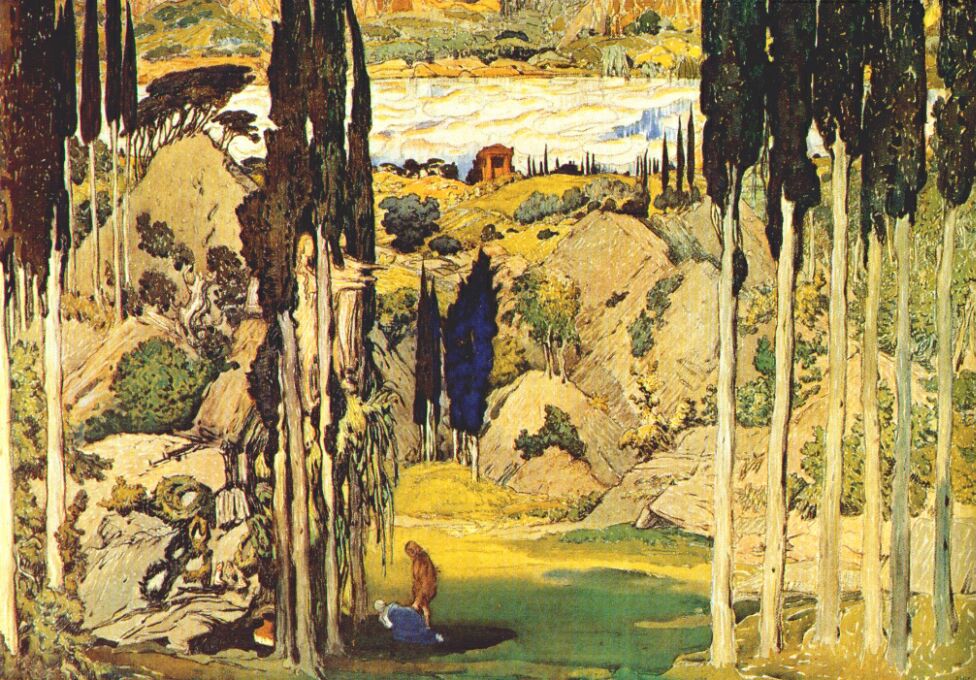

Léon Samoilovitch Bakst, set design for Ravel's Daphnis et Chloë, 1912

Source: Wikimedia Commons

As you read about the passing of the seasons and the growing love of Daphnis and Chloe, it is easy to forget that the landscape Longus is describing is actually made up of the estates of rich men, living away in the city, and that Daphnis and Chloe are actually slaves. Daphnis works on 'a very splendid property: it had mountains abounding in game, plains fertile in wheat, gentle slopes with vineyards, pastures with flocks, and a long stretch of shore where the sea broke on the softest sand.' The last part of the novel, Book 4, begins with the news that the Master is returning to look over his property, including a large pleasure ground, containing cypresses, laurels, pines, and plane trees, fruit trees (apple, pear, pomegranate), beds of roses, lilies and hyacinths, and wild flowers: violets, narcissi, pimpernels. In a description which reads like a blueprint for eighteenth century landowners, Longus writes that 'from there, a wide prospect opened over the plain and the sea beyond, and it was possible to see the peasants minding their flocks and herds, and the ships scudding across the bay - that view was another of the delights afforded by the pleasure-ground' (trans. Ronald McCall).

In the end, it turns out (to no great surprise) that Daphnis and Chloe are not the children of peasants - both had been exposed at birth by their real parents, suckled by a goat and a sheep, discovered and then brought up in the countryside. But after they marry they return to their rustic idyll and own sheep and goats in great number. They name their children Philopoeman ('friend to shepherds') and Agele ('herd'). It is a happy ending but to a modern reader it seems a shame that they go on to 'beautify' the Nymphs' cave with pictures and 'let Pan have a temple for his home instead of the pine tree'. Such artifice is of course in keeping with the pastoral genre and indeed the entire novel is a kind of ekphrasis: its preface explains that Daphnis and Chloe is a story the author saw one day while he was out hunting in Lesbos, depicted in a painting, hanging in a grove sacred to the Nymphs.

Titian, The Three Ages of Man, c1512

It has been suggested that this may show scenes from Daphnis and Chloe

Source: Wikimedia Commons

There are other things I could say about landscape in relation to this book, but I'll confine myself to noting that there are three points in the story where aetiological myths are poetically retold to explain natural phenomena: the call of the wood pigeon, the origin of pan-pipes and the source of echoes. Chloe first experiences an echo while listening with Daphnis to the singing from a passing boat, down below them in a deeply curving bay. Behind the level pasture where they stand there is a hollow coomb which receives the sounds and 'like a musical instrument' repeats them back again. Chloe promises Daphnis ten kisses if he will tell her the origin of this phenomenon and so he begins his story, explaining that 'there are many kinds of nymphs - ash-tree nymphs, called Meliae, oak-tree nymphs, called Dryads, and nymphs of the marshes, called Heleioi. All are fair, all are makers of music. Echo was born the daughter of one of these ... the Muses taught her to play the pan-pipes and the flute, to sing to the lyre and the cithara.' She shunned mankind but Pan grew jelous and drove the shepherds and goatherds mad so that they tore her to pieces, still singing. Earth gave these shreds of music shelter and now they are able to portray the sounds of people and animals, just as Echo once had done. 'When Daphnis ended his story, Chloe gave him not ten but ten-score kisses - for the echo had all but repeated what he said, as though to witness that he told no lie.'

No comments:

Post a Comment